A unique Atlantic Wall site

The Atlantic Wall is a vast 4,000 km long coastal defence system built by Nazi Germany during the Second World War to protect itself from an Allied landing.

A strategic location

In 1942, the German army identified the town of Azeville, set back from the coast a few kilometres from Sainte-Mère-Eglise, as a strategic base. A battery that was invisible from the sea!

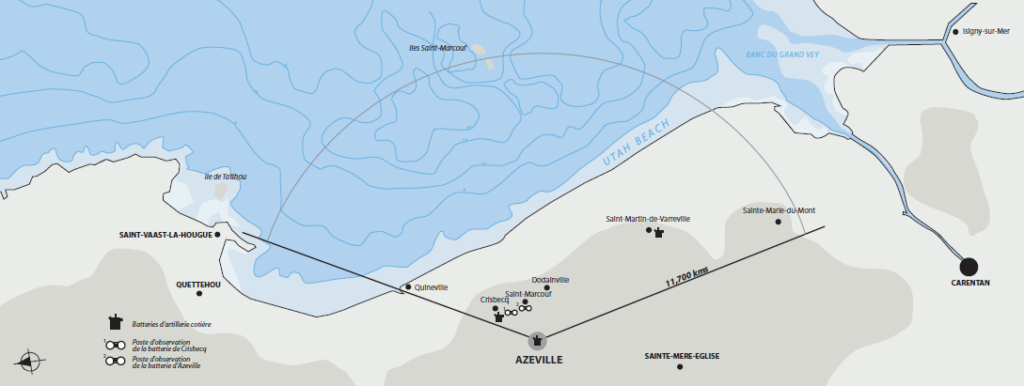

Located 4 km from Gougins beach (Saint-Marcouf), the Azeville battery was in charge of protecting the east coast of the English Channel from a possible landing. Its guns covered an area stretching from the Bay of Saint-Vaast-la-Hougue to the Bay of Veys.

A unique complex

Between 1943 and 1944, four powerful reinforced concrete casemates designed to protect the artillery (105 mm Schneider 1913 guns), were built under the supervision of the Todt organisation.

The site was also equipped with two anti-aircraft guns.

The complexity of this military space lies in the impressive network of concrete tunnels and covered trenches extending for over 800 metres. It provided shelter for men and ammunition.

A German garrison at the heart of a Normandy village

Around 170 men were under the command of Hauptmann Hugo Treiber.

So they lived in the local community for two and a half years in direct contact with the population of 115.

Over two years of construction for a three and a half day battle

On the morning of 6 June 1944, the battery went into action, shelling the Utah Beach landing sector.

Finally, on 9 June, after intense fighting, the garrison surrendered to the American soldiers of the 4th Division.

Now a tourist spot

In 1994, as part of the fiftieth anniversary of the D-Day landings, the Département de la Manche became the owner of the concrete structures.

Enlightened by rigorous historical research, the Department opened the site to the public.

The Azeville site is part of the network of sites and museums managed by the Département de la Manche.

Discover the Azeville Battery in video

Transcription of the video

Duration 11 minutes 37 – Music and video title: “Discovery of Azeville’s Battery” with Marlène Deschâteaux.

Aerial view of the site with a drone.

Marlène Deschâteaux: “Welcome to the Azeville Battery, a site from World War II, particularly associated with the Atlantic Wall.

I am going to take you zon a tour of this site, but first, a little context. Between 1940 and 1941, the German army has a very offensive position in the West Europe. Starting from the end of 1941, the idea of a new defense system is born, that will allow to send more men to to the East and to keep only a small fraction of them to the West, but to ensure the defense of European West coast. This system would later be called the Atlantic Wall. The Atlantic Wall stretched from Norway to the French-Spanish border and measured about 4,000 km. Azeville is part of this Atlantic Wall; it is a support point in the hinterland.”

So, what is a battery? A battery is simply a set of cannons. Here, we’ll find four Schneider cannons from 1913. They would later be protected by fully concrete casemates.

If you want, follow me, let’s enter the Azeville Battery site. Let’s go!”

Moving through the underground tunnels, sounds of footsteps on gravel.

Marlène Deschâteaux: “The underground tunnels of the Azeville Battery are 350 meters. By the end of 1944, there were about 800 meters of underground galleries, allowing the garrison to move from one point to another while staying sheltered.”

View of ammunition storage compartments, then arrival in a magazine that now houses a permanent exhibition on the German garrison of Azeville.

Marlène Deschâteaux: “In 1944, this room was supposed to serve as an ammunition storage. But, as I mentioned earlier, the Germans were severely lacking ammunition. Therefore, this room never had this function. The ammunition was stored directly near the casemates and cannons.

Here, there was a telephone directly connected to the casemates’ telephone. The two soldiers locked in this room would receive the call, prepare the necessary shells, and pass them not through the door (which was closed) but through this shell chute. The idea was to prevent a fire from spreading.

If the two soldiers are locked in here, how do they get out? The TODT organization, which designed the plans for these batteries, thought of creating an emergency exit. You have to remove the exposed stones, and there was a whole ladder system that allowed the Germans to exit if needed.

A few years ago, we were lucky enough to recover the diary of Commander Treiber, which allows us to document a lot about this site’s history. We discover a man who was aware that the villagers of Azeville were in danger because of the installation of a battery in their village.

You have to imagine that, overnight, 170 men arrived in Azeville, a small village with only 115 inhabitants at the time. So there were more Germans than French people in this town.”

Music, aerial view of the site and the village, then a return to the underground view.

Marlène Deschâteaux: “Let’s continue, we’ll go to a shelter for the personnel.

This room could serve as a dormitory, thanks to chains attached along the wall. Then, there were three bunk beds. In total, the room could accommodate up to 12 men as a dormitory.

The purpose of this room was primarily to provide shelter for soldiers during outside bombings. In case of an attack, the armored doors and windows would be shut. While they were completely sealed inside, the soldiers still had ways of communicating to know what was happening outside. There was already a telephone exchange. Then, there was an acoustic tube system that allowed communication with the man in the nearby lookout post. Finally, there was a periscope. You could see what was going on outside, while remaining almost invisible to anyone outside.

Since the room was sealed, a problem would arise very quickly: the lack of air or possibly increased pressure if air were brought in.

So, they thought of installing arm-operated fans with filters to filter the air. But if they brought in air without quickly releasing the pressure, it would lead to the death of the soldiers. That’s why they also installed pressure relief vents in such rooms to evacuate pressure. Ultimately, the men could stay several hours here, sheltered and waiting for the outside bombings to end.”

The guide has exited the tunnels. She is now at the northernmost part of the site and heads toward a gun emplacement. The site is windy this day.

Marlène Deschâteaux: “So, we’ve walked about 350 meters of underground tunnel. We started from the Mess and have now reached the northern part of the site.”

View of the casemates via drone, then on a gun emplacement.

Marlène Deschâteaux: “In March 1942, four cannons were installed here, forming the Azeville Battery. They were initially placed in open gun emplacements, which allowed them to defend the site. Around them, you’ll find small ammunition storage cells.

When the first casemate was finished, the cannon that had been on an emplacement was moved to be sheltered inside a casemate.

If you want, you can come closer to better understand the site’s geographical situation and its layout. [View of the site’s map.] We started from this reception building, crossed through the underground section, and came out here outside, on this emplacement. The other three emplacements have completely disappeared today. All the dashed lines indicate where the underground tunnels used to be, but they have completely disappeared now. Let’s continue, and we’ll enter this casemate.”

Music and aerial view of a casemate and particularly the gun emplacement on its roof. Then a view of one of the casemate’s facades.

Marlène Deschâteaux: “You can see some damage caused by the battle between the Allies and the Germans at this site and the few shells that managed to partially destroy these concrete casemates.

You have to imagine that it took about 200 men to build a casemate like this, and these were not the soldiers of the German garrison. Very quickly, prisoners of war from the East were brought in to participate in the construction.

The first casemates were poured in the spring of 1943, and the last one was completed in February 1944, just a few months before the D-Day landings.”

The guide is now inside a casemate, crossing a corridor to reach the firing chamber.

Marlène Deschâteaux: “The four casemates on this site are identical. They are all built the same way. In each casemate, we first find two ammunition storage rooms, then the firing chamber with the cannon, and finally, behind, a shelter for personnel and a post for a machine gun.

The uniqueness of the Azeville casemates is that they were camouflaged. The idea was to deceive the enemy. The two northernmost casemates were camouflaged with trompe-l’œil images of ruined houses, and the two casemates further south were camouflaged with a mound system. The idea was not to be detected.

[Photograph of an aerial view of the site in 1944.]

When we look at aerial photos taken by the Allies a few days before the landings, we see that this system didn’t work and was quite naive.

A battery is supposed to defend the coast. From here, you can’t see the sea at all. We are about 5 km from the coast.”

Music, aerial view towards the coast, then a 1944 photograph showing a casemate still equipped with its cannon and a view of the battery’s firing field plan.

Marlène Deschâteaux: “The Azeville Battery’s cannons had a range of 12 km, which gave them a firing range from the Saint-Vaast bay to the Baie des Veys, passing by the Saint-Marcouf islands.

Azeville wasn’t alone in defending this sector; it was paired with the Crisbecq Battery and the Saint-Martin-de-Varville Battery, which were responsible for defending the entire sector. The construction of the Azeville Battery took about two and a half years to fortify the whole site, including the underground tunnels and the sheltering of the cannons in casemates. [Photographs of workers and soldiers involved in the site’s construction.]

During the landings, it was only active for three and a half days. That may seem short, but it was still a very long time during the D-Day period, as it greatly slowed down the Allies.”

Music, aerial view and return to the guide, then the firing chamber and a shell head.

**”One major event I want to tell you about is when the USS Nevada, a huge battleship, bombarded this site and managed to hit this firing chamber. This shell was only discovered in 1994 before the site opened to the public. It destroyed the cannon in this room, destroyed the wall, and killed the fifteen or so men inside this room.

Here we can only see the head of a shell similar to the one that pierced this casemate through and through. Just the size of this shell head is enormous, and it gives us an idea of the damage it could have caused. We see that the blast deformed the door here. In fact, the men inside perished because of the blast from this shell passing through.

The shell then pierced the armored window and finished its journey outside, just here.”

Music and view of the outside, where the shell was found.

“After only seeing the head of a shell, here we have a photograph of the 356 mm shell found in 1994 just outside this casemate.”

Conclusion with a view of the site, the guide, and the logo of the Manche Department, the site’s owner.

“So, to summarize: the construction of this battery took two and a half years. It was active for three and a half days of battle, which ended on June 9 at 14:00 at this site. It marked the end of the military life of the Azeville Battery. However, we mustn’t forget that this wasn’t the end of the war in France and Europe. We would have to wait several more months to see the end of the war.”